Protecting Armenia from Toxic Pollution: Why Independent Monitoring Matters

4 min readIn2014, ONEArmenia raised $31,316 for “Let’s Protect Armenia from Toxic Pollution”, a campaign aiming to fund research on the impact of mining in Armenia. Last Tuesday, the American University of Armenia’s Center for Responsible Mining presented their findings to the general public.

Why is this important?

Despite its relatively small surface, Armenia has over 400 active mines on its territory. The mining sector still represents over 50% of the country’s exports, and new mining projects regularly cause controversy (see civic protests over Teghut or more recently the Amulsar Gold Mine). The industry advocates argue that mining creates jobs and substantial economic gains for Armenia, while concerned citizens point out the impact that mining has on the environment and on the health of nearby communities.

It ought to be mentioned here that mining, despite being the biggest recipient of foreign direct investment in Armenia, only contributes to 3% of the country’s GDP. The sector relies on finite resources, is regulated by legislation that’s been described by some as lax, and imposes a burden on other economic sectors such as tourism or agriculture.

Having access to independent monitoring of air, water and soil quality is of crucial importance to people living near mines. It’s also a first step towards having “responsible mining” used as an accurate description of the reality of the industry in Armenia.

AUA’s Process

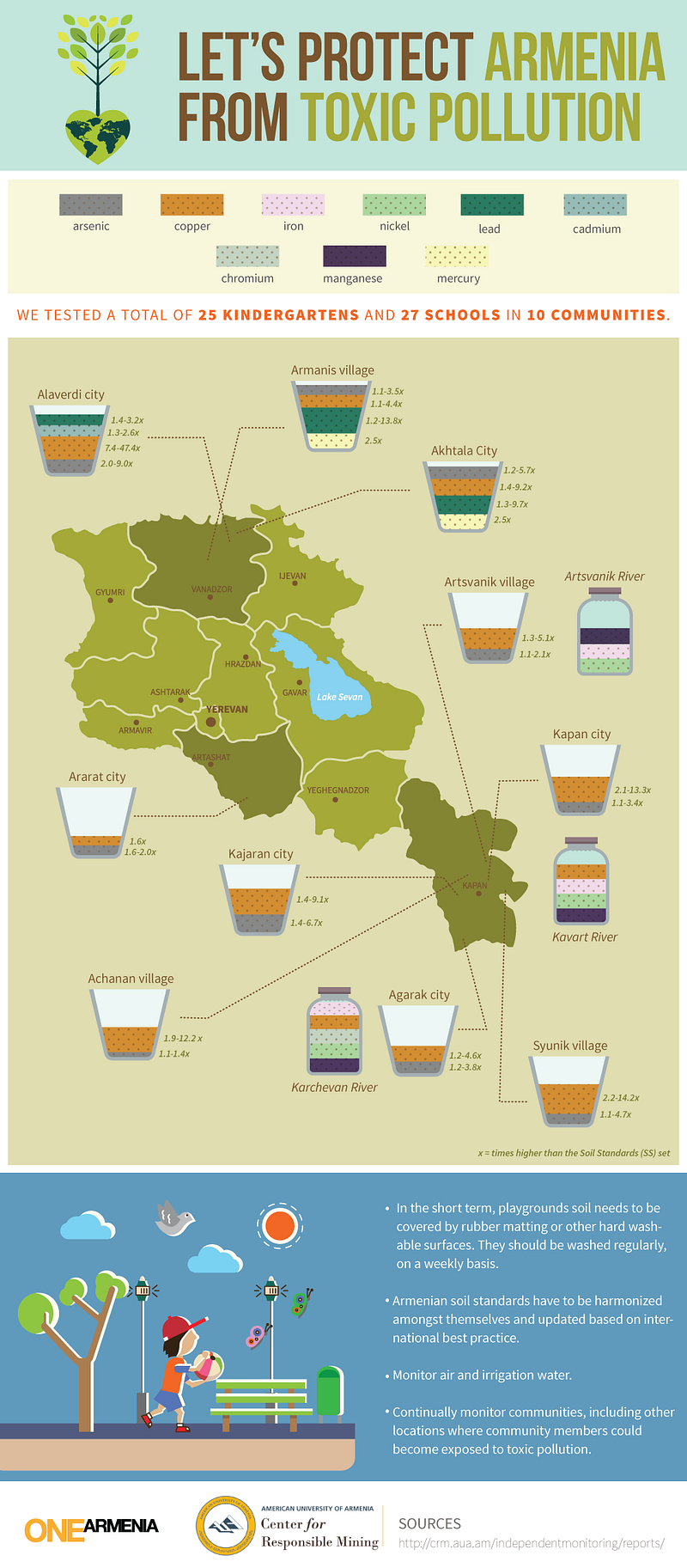

Over the past year and a half, the AUA Center for Responsible Mining has been gathering water and soil samples in schools and kindergartens across the country.

Thanks to your donations, and the generous pledge by the OSCE and UNDP, the AUA Center for Responsible Mining was able to recruit research specialists, establish protocols for sampling and testing, and map 150 communities located within 5 kilometers of a mining, metal processing, or mineral tailings facility.

In total, 10 mining communities, home to 92,130 people, were tested. The AUA Center for Responsible Mining worked closely with the local authorities to get the necessary permits, and when their research was completed, went back to present their final findings to each community.

Findings

All the reports are available on their website in both English and Armenian.

They gave us at least one piece of good news: none of the drinking water samples tested presented any problem. This is due to the fact that the water sources tested were located either upstream, or sufficiently far from the mining activities, thus avoiding contamination.

On the other hand, many of the soil samples that were tested for presence of arsenic, cadmium, copper, lead and mercury showed concentrations of heavy metals in the soil, some of which may have detrimental effects on human health.

According to the reports, lead is a heavy metal of concern in Alaverdi, Akhtala and Armanis, which raises immediate alarm for the health of the children living in those areas. At the public presentation on Tuesday, researchers from the School of Public Health at AUA highlighted how lead affects the mental development of children. Dzovinar Melkom Melkomian, of AUA’s Center for Health Services Research and Development, made a point of noting that there is no level of exposure to lead which can be considered safe for children.

Arsenic is a heavy metal of concern in all the communities that were tested, although the reports can’t establish that the level of arsenic in the soil is due specifically to industrial or mining activities in the area.

Each report also provides detailed background information on the mining activities conducted in these areas, such as the type of ore extracted, the location of the tailings, and the companies responsible for them.

Where do we go from here?

The reports do include recommendations, but it is now up to each community to take matters in their own hands in order to protect their children from the impact of nearby industrial activities. In all its reports, the AUA Center for Responsible Mining recommends that school and kindergarten playgrounds be covered in asphalt or rubber (or any other washable surface) to minimize children’s exposure to lead, and in certain cases copper and arsenic.

But the research and monitoring should not stop here. The AUA Center for Responsible Mining’s extensive research did not include testing air samples or irrigation water. They recommended investigating the Debed, Akhtala, Voghji and Kavart rivers for heavy metal pollution, as their suitability for irrigation might be in question. Likewise, the AUA Center for Responsible Mining recommended including other metals (such as chromium, zinc, nickel, manganese) wherever possible in subsequent studies. Going forward, research should be conducted in order to create a soil quality database, using this study as a baseline.

The AUA Center for Responsible Mining also advocates for modifying the Armenian Soil Standards — the official allowed concentration for different metals in the soil. For several of the heavy metals monitored in this study, the Armenian Soil Standard is one of the most stringent in the world, stricter in many cases than those enforced in Europe or Northern America. “What is wrong is strict standards?” — you may ask. As Alen Amirkhanian, director of the Acopian Center for the Environment, noted on Tuesday morning, standards that are not realistically enforceable allow mining companies to dismiss the importance of abiding by those standards, and to diffuse responsibility.

To learn about the whole environmental monitoring effort and read the protocols and reports, go on the AUA Center for Responsible Mining’s website — all of the results have been made publicly available in Armenian and in English.